When you are having tests for a possible cancer, there are two important things to find out. Firstly, your doctor needs to discover what type of cancer it is. This is very important, as different types of cancer respond to different treatments. Secondly, they need to find out how far the cancer has grown and whether it has spread. There is more about this in the section on staging bile duct cancer.

You are likely to need various tests to diagnose bile duct cancer. Usually, you see your GP first, who will examine you and may ask you to have:

- a full blood count (FBC) to measure your red blood cell, white blood cell and platelet levels

- a liver blood test

A liver blood test used to be called a liver function test. It looks for ‘markers’ in the blood that indicate a problem with the liver. It also measures blood levels of proteins and liver enzymes.

Any abnormal results in your blood tests may suggest a problem with the liver.

If there are any concerns, your GP will refer you to a hospital specialist for further investigations. Bile duct cancer is rare, so if this is suspected, you may need to travel to a regional centre that specialises in liver, pancreas and gallbladder disease. The specialist will ask about your medical history and arrange some tests, including blood tests, if you haven’t had these done already.

You may have any of the following tests to diagnose bile duct cancer:

This uses soundwaves to make up pictures of the bile ducts and surrounding organs. It is quick and painless. This is a common test for several types of liver cancer. There is more about having an ultrasound in our info on general liver cancer tests.

A CTscan takes a series of X-rays in cross section and builds them into a 3D image. It’s completely painless and takes about half an hour.

There is more about having a CT scan in our info on general liver cancer tests.

MRI uses magnets and radio waves to produce images of the inside of the body. MRI scans show soft tissues more clearly than CT scans.

MRIs are painless and take about 30 minutes. But they are very noisy, so you may have headphones or earplugs and can bring your own music to listen to. There is more about having an MRI scan in our info on general liver cancer tests.

PET stands for Positron Emission Tomography. In bile duct cancer, a PET scan can help to show if the cancer is in any nearby lymph nodes. Doctors also sometimes use it to check for signs of the cancer coming back.1

You have an injection of a ‘radiotracer’ (a very small amount of a radioactive substance) into a vein. The tracer collects in cells that are very active, like cancer cells. It can help to show whether any abnormal looking areas are cancerous or scar tissue from something else.

The scan takes between 30 minutes and an hour. You have to be there an hour before it starts to have your injection. You need to be on time as the injection decays and the scan may be cancelled if you’re late. There is more about having a PET scan in our info on general liver cancer tests.

This stands for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (say: kol-an-gee-oh pank-ree-at-og-raf-ee). This special type of MRI scan produces pictures of the gallbladder, bile ducts and pancreatic duct. It helps doctors to clearly see the bile ducts and find out whether any issues are caused by inflammation, infection or cancer.

An MRCP scan takes about 40 minutes and is completely painless. You can’t eat or drink for a few hours beforehand – your doctor will tell you exactly what time you need to stop. You can usually take any medication as normal, but check with your doctor if you are concerned, or if not eating and drinking is difficult because you have diabetes.

To have this scan, you change into a hospital gown. As this type of test also uses MRI, you have to remove all metal items, as for MRI (see above). The radiographer may give you some pineapple juice to drink. This contains manganese, which helps the scan pictures to show more clearly.

As with MRI scans, MRCP scans are noisy, so you’ll have headphones or earplugs. You will need to hold your breath at times, when the radiographer asks you to and you may feel hot and tingly during the scan, which is normal and nothing to worry about

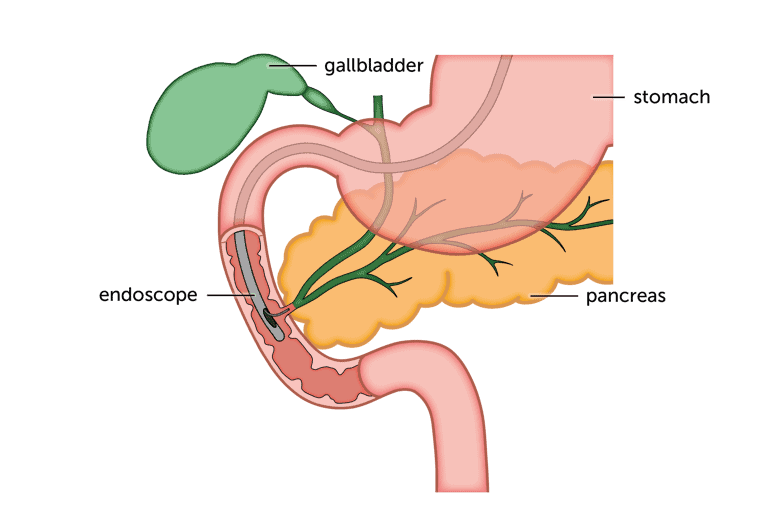

ERCP stands for ‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography’ (say: en-doss-kop-ik ret-row-grade kol-an-gee-oh pank-ree-at-og-raf-ee). The doctor looks at your bile ducts from the inside, through a long tube passed down your throat, through your stomach and into the small bowel. The tube is called an endoscope and has a light and a camera.

The doctor can also operate very small instruments through it to take tissue samples (biopsies).

A cholangioscopy (say: kol-an-gee-oss-kop-ee) means that the doctor puts an even smaller tube directly into the bile ducts, through the endoscope.

They can check for any abnormal looking areas and take biopsies from right inside the ducts.

You have antibiotics before an ERCP to help prevent infection. The test itself can take up to 2 hours.

You can’t eat or drink for 6 hours beforehand, so your stomach and the first part of your small bowel (intestine) will be empty.

You have a general anaesthetic or a sedative injection just before your scan. A general anaesthetic will put you to sleep, a sedative will relax you and make you drowsy. Do remember that you won’t be able to drive yourself home if you’ve had a sedative and should have someone stay with you overnight at home if you live alone.

Before putting the tube in, the doctor will spray anaesthetic on the back of your throat. This numbs it and makes it easier for you to swallow the tube. Once the tube is in place, the doctor injects a dye that shows up on X-ray. This helps them to see whether the bile ducts are blocked anywhere. If they are, they may put in a small plastic or metal tube called a stent to re-open the blocked duct and let the bile drain.

You may need to stay in hospital overnight after an ERCP or cholangioscopy. If you are going home, you may have to stay a while until the sedative or anaesthetic has worn off. You shouldn’t eat or drink for an hour, until the anaesthetic spray has worn off, as it can affect your ability to swallow.

This is an ‘endoscopic ultrasound scan’. It’s similar to ERCP, except for a very small ultrasound probe attached to the endoscope. So you can have an ultrasound scan of the gallbladder and bile ducts done internally, through the wall of the small bowel. The doctor can also take tissue samples (biopsies) during the test.18 This test is used to diagnose other types of liver cancer, so there is more information about having an endoscopic ultrasound in our liver cancer tests section.

This stands for ‘percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography’. PTC shows up any blockages or abnormalities inside the bile duct.

Percutaneous (say: per-kew-tane-ee-us) means through the skin. Using a needle, the doctor injects dye to show up the bile ducts more clearly on an X-ray. They can also take a tissue sample (biopsy) from the liver or put in a stent to help drain bile.

See our general liver cancer tests section for more about having PTC.

A biopsy is a small sample of tissue. Your doctor can remove this from the bile duct during a PTC or ERCP (see above). It then goes to a medical laboratory to be examined for signs of cancer.

Your doctor may use an ultrasound or CT scan to ‘guide’ the biopsy and make sure they take tissue samples from the right place.

See our general liver cancer tests section for more about having a biopsy.

A laparoscopy is really a small operation. While you are asleep (under a general anaesthetic), the doctor makes a small cut (incision) into your tummy (abdomen) and uses a tube with a camera attached (the laparoscope) to examine the area.

As with an endoscopy, they can use small instruments through the tube to take tissue samples if they see anything that looks abnormal.

See our general liver cancer tests section for more about having a laparoscopy.

This means taking a sample of your cancer and testing it to see which particular gene changes the cancer cells carry. Cancer cells have changes in their DNA that help them survive and grow uncontrollably. The most recent developments in cancer treatment target these changes – so are called targeted or biological drugs. To know which of these are likely to work for you, your doctor has to know whether your cancer cells have the target that each drug attacks.

There is more about targeted treatment for bile duct cancer in this section. And more about what targeted treatment is in our general info on liver cancer treatment.

You are unlikely to get any results from these tests straight away. You usually have an appointment with your specialist a week or two afterwards, to go through the results.

After your tests

Waiting for test results can be nerve wracking. It could take a week or two and that may seem like forever. There’s no right or wrong way to deal with this situation. Many people try to carry on as normal – others find their concentration is too poor. Try not to bottle up how you are feeling. If you don’t feel you can talk to relatives or friends, a counsellor may help. Take a look at our advice on looking after your mental health.

In the meantime, be reassured that you haven’t been forgotten – work on your case is going on. Scan reports have to be made and sent to your specialist for review.

If you’ve had biopsies taken, the sample may need to be ‘stained’ and that takes a few days. It means that a dye is put onto the sample that helps to show up the cells more clearly under a microscope.

A team of specialists may need to look at your results to decide the best course of action. This is called a ‘multi-disciplinary team’ or MDT for short. It may include a surgeon, medical cancer specialist, specialist nurse, pathologist (specialist in studying cells and biopsies) and a radiologist (an expert in reading scans and X-rays). Once they’ve met and discussed how best to treat you, you will have an appointment to go through your diagnosis and any planned treatment.

When you go to get your results, it’s a good idea to take someone with you. This isn’t only for moral support. It’s so that there are two of you to remember what’s been said. Your relative or friend could take notes for you and remind you of any questions you particularly wanted to ask. The next page in this section has some suggestions for useful questions for your doctor.

Content last reviewed: October 2022

Next review date: October 2025